Lost Times

The cottage we’re renting for a week in June is on the Kingston Lacy estate in Dorset and is owned by the National Trust. Pink and thatched, it has low ceilings and doorways on which my husband whacks his head at frequent intervals. To one side of it is an overgrown orchard; behind, a patch of grass where three rabbits have taken up residence. That first evening, we sit in the garden, watching the rabbits and listening to birdsong. A short stroll down a lane takes us to a pub, the Vine. This holiday is sandwiched between my finishing a novel and the approaching visit of our eldest son and his family, who live in San Francisco and who are to stay with us for a month.

It’s one of the hottest weeks for years. The day after we arrive, we decide to walk to Kingston Lacy. We study our map and hope, with what turns out to be misplaced confidence, that a path marked ‘Entrance Copse’ will lead us to the house. When we reach it, it’s marked ‘Private’ so we head on. We’re walking through woodland. Sunlight pours between the branches and dapples the ground. It’s getting hotter and hotter and we begin to feel as if we’re circling the house yet are doomed never to reach it, like an ill-fated duo in a fairy tale. Eventually some dog-walkers point us in the right direction and we find, at last, an entrance. The trees peel away and the sun beats down hard as plod up a long, winding driveway. By the time we reach the house, we don’t give a fig for its charming Italian-inspired beauty and head straight for the restaurant, where we gulp down water and tea.

I was born in Wiltshire and brought up in Hampshire. When I was a child, we never went abroad on holiday but stayed in seaside towns in the south and west of England – Lyme Regis and Mevagissey, Torquay and Ilfracombe, and the Isle of Wight.

I have two brothers and a sister: there are less than eight years between oldest and youngest. My parents did not own a car and we lived in an out of the way part of Hampshire, where buses were infrequent and often crowded. Our longer journeys were taken by train. Going on holiday, we’d rise early in the morning and a taxi would take us to Andover station. My father would find a compartment in a carriage that would take the six of us and negotiate any changes of train on the journey. He had a habit of deciding, on a whim, to nip out to buy sweets from a platform kiosk when the train stopped at a station. My mother would implore him not to – my father always kept the tickets and she had a terror of the train starting up again before he returned, leaving her stranded in the carriage with four small children and no tickets. But somehow, he always made it back in time.

We stayed in Bed and Breakfasts or small hotels. Often, I’d have to share a double bed with my younger sister, who had a way of sprawling horizontally across the bed, so we’d end up fighting. The small hotels were, I think, looking back, of varying quality. There was the one where we all came down with food poisoning. There was the one where tar from the beach was trodden into the carpet from some child’s shoes and the proprietor told my mother off, to her great mortification. But there were kind places too – the guest house where the proprietor lent my sister and I pyjamas and jerseys because my father had decided to make a day trip into a weekend (another whim), or the one where they found us books to read because the weather was bad. Occasionally, we stayed in a rented house, but mostly not, because the whole point of a holiday for my mother was a respite from housework and cooking. Once, excitingly, we stayed in a camping coach, a converted railway carriage in a railway siding – a more basic forerunner, perhaps, of the decorative caravans and glamping popular today.

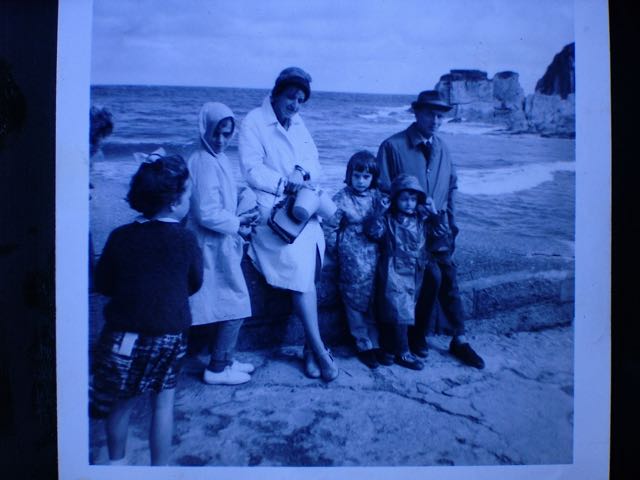

I adored going on holiday (still do). I’d save up my pocket money for weeks beforehand, in a cocoa tin on which I’d pasted pictures from a comic. I’d spend my ten shillings on a souvenir – a shell-encrusted box, a statuette of a ballerina or mermaid, something like that. I dreaded travelling by bus because I always felt sick, but loved train journeys, particularly the Devon/Cornwall line, where the train runs along the coast and you can see the sea. As soon as we could after arriving, we’d run to the beach, where the four of us would paddle and make sandcastles and collect sea-glass and shells and explore rock-pools. Photos of those holidays show us girls in plastic macs and transparent plastic headscarves – I guess global warming hadn’t set in at that time. There were holidays we abandoned because of the weather. But I don’t think we children cared about the rain.

It’s different now. Iain and I drive to Dorset. The frustrations of travel are no longer missed connections but lengthy traffic jams. We stop at a service station to buy coffee instead of making that precarious dash to a station kiosk. Our cottage has everything you’d want – cotton bedding, rather than the slippery nylon sheets of 1960’s B & B’s, a well-equipped kitchen, a TV and DVD for if it rains. We eat out far, far more often than we ever did when we were children.

I carry with me, many decades later, those images of perfect childhood holidays. So during our week in Dorset, a few things disappoint. Sandbanks is not the idyllic wild place of sand-dunes that I’ve recalled with affection for half a century, but a town of millionaires’ houses and very steep car-parking charges. Names on fingerposts conjure half-forgotten memories – is this the remote place, with not a house or a single other person in sight, where, in my teens, I once waited, rather anxiously, for a bus after visiting a friend at an army camp on Salisbury Plain?

I still love this part of the world. My spirits lift whenever we head south-west. Just as a Scot yearns for mountains and misty glens, there is a part of me that longs for chalk streams and meadows. I love the way history has soaked into the landscape. The Iron Age fort at Badbury, alive with butterflies and wild orchids; the ruins of Corfe Castle, still shocking in its annihilation 370 years after its destruction by Parliamentary soldiers in the Civil War. And the countryside, with its sparkling rivers, high plains, rolling hills and steep valleys.

Driving back to Cambridge, sitting in yet another traffic jam, I recall the green tunnel of All Fools Lane, where we walked in the heat of an afternoon, light spilling in fragments on to the badger setts in the high earth walls of the tunnel, giant bracket fungus sprouting from a fallen tree, a hidden world, and I start to make plans for our next return.